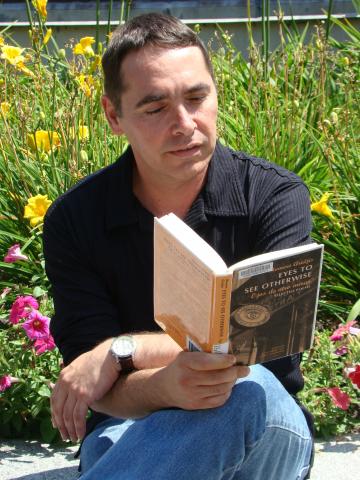

Eyes to See Otherwise is a careful selection that offers a precious panoramic view of Aridjis’ poetry in Spanish from 1960 to 2001, with English versions by thirteen well-known translators. It documents the spiral progression from the clean free verse of “Unfolded Eyes”, Aridjis first book in 1960, to the complex meditative tone of his 2001 book, “The Eye of the Whale.” In the often wet Bowdoin summer, when there is some time for tranquility, each of these poems leaves me with a quiet sense of wholeness:

Over the month of June the rain is falling

. . .

Deep in your heart the young girls laugh (7).

This double awareness of what is going on around you and within you at any given moment is one of the “eco-traits” in Homero Aridjis’ poetry, and probably a reason why he is one of the most widely read living Latin American poets today. His having been president of International PEN, the worldwide association of writers, from 1997 to 2003, helps, too, as well as his activism in favor of the environment in Mexico and in favor of free speech around the world.

The motif of the double is all over the book. Mirrors, two-edged identities, woman within man, daughters in fathers, self-portraits, the otherness in the title itself, all add to this duplicity. And it gets amplified by its being a bilingual edition. Reading a poem in two languages, like listening to a song in two versions, enhances your awareness of how the piece is built and offers you insights into how two voices approach the wor(l)d. One particularly acute case is Aridjis’ attempt to capture a verse by Shakespeare (“I met the night mare,” quoted by Borges) in a Spanish that loses the pun: “la yegua de la noche” is just the night compared to a literal female horse. But then, translated back into English by George McWhirter, the double-meanings are restored:

The night mare

made him come in dreams

and kiss the air (227).

Wet summer dreams, indeed.

Aridjis draws from the Mexican, Hispanic, and classic Western imaginaries to weave a serene poetry of epiphany and deep connection to nature: “Water speaks in pure clarity” (81). From angels to Aztec goddesses, from the Spanish Civil War to the extinction of the gray whale, from the erotic to the communal, this poetry maps the contemporary experience of an interdependent world. Its prophetic, introspective and tender tone does not exclude the monstrous and the erudite. The book joins the revision of values, of how the human –the eye, the I– is de-centered, in an era of environmental urgency.