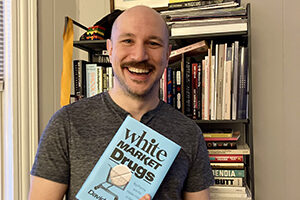

I confess that I read so much for research and teaching, that I end up reading embarrassingly little for pleasure. That’s why I was excited when I was asked to contribute to the “Bowdoin Reads” series, as I told myself that I couldn’t read anything that deals with my current work. I ended up choosing David Herzberg’s White Market Drugs, a historical survey of how the U.S. government has regulated addictive medications over the twentieth century.

As a kid growing up in suburban Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, I got all the ‘war on drugs’ rhetoric: ads comparing getting high to frying your brain and middle school visits by police officers in the D.A.R.E. program. Journalist and scholarly work since that time has shown how the war on drugs has worked hand-in-hand with what Michelle Alexander called “The New Jim Crow,” using small-scale drug offenses to over police and undersupport Black and brown communities. Herzberg tells the story of the other side of U.S. drug policy—of the class of patients who were allowed access to equally powerful “medicines” through mostly legal (and rarely policed) channels. As Herzberg describes in his introduction, the division between a prescription market for addictive medicines and the illegal market for drugs is the result of a century of policy decisions that have determined who is a worthy of care and who deserves to be punished. These value judgments were laid out in U.S. government bureaucracy—creating one agency (the Food and Drug Administration) to protect lawful consumers from predatory pharamaceutical companies and a second agency (the Federal Bureau of Narcotics) to punish criminal users. These value judgments were also cultural, creating arbitrary distinctions not only between medicines and drugs, but also between chemically-dependent victims and criminally liable drug addicts.

White Market Drugs paints an impressively totalizing picture. The book covers three eras of government regulation of addictive pharmaceuticals—opiate crises from the 1890s to the 1950s, sedative and stimulant crises from the 1920s to 1970s, and the reemergence of all of these drugs after pharamaceutical deregulation beginning in the 1990s. One of the more surprising things I learned from reading this book was how middle class and largely white consumers have traditionally had much more access to mood-altering chemicals than people forced into illegal markets. Herzberg argues that these crises persist through a consistent will-to-forget. For a book on 100 years of government regulation on the pharmaceutical industry, White Market Drugs was a pretty fun read. Herzberg provides a lot of illustrations of mid-century drug ads that are visually really compelling. Although regulatory agencies seem to come and go in the narrative, Herzberg does a great job explaining the overlying logic that has overdetermined our drug policy. And although it wasn’t the most obvious choice for escapist reading over break, I will never look at a prescription pad the same way!

“These value judgments were also cultural, creating arbitrary distinctions not only between medicines and drugs, but also between chemically-dependent victims and criminally liable drug addicts.”

Important review. Thanks – something for my bookshelf.