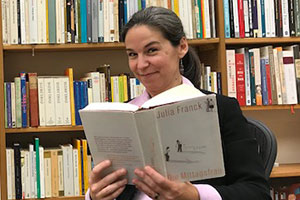

I am currently reading Julia Franck’s novel Die Mittagsfrau for the second time as I prepare a talk on it for an upcoming conference. I first read the book in 2008, when I directed an honors project that focused on its depictions of gender and sexuality in Germany during the turbulent first half of the 20th century. Winner of the 2007 German Book Prize, Franck’s novel follows the life of Helene Würsich from her childhood in the Saxon town of Bautzen, where her dreams of becoming a surgeon are clouded by the death of her father and the mental instability of her Jewish mother, through a phase of sexual and intellectual experimentation and freedom in 1920s Berlin, to her oppressive marriage to a Nazi engineer. Forced to pass as a non-Jewish German named Alice in Nazi Germany, Helene suffers the racist taunts and sexual assaults of her husband Wilhelm and unwillingly bears and raises their son, Peter, only to abandon him in a train station at the end of the Second World War.

As a scholar of the Weimar Republic and as someone who is currently working on how Weimar Berlin is depicted in contemporary fiction and film, I appreciate Franck’s detailed, well-researched descriptions of the German capital and its vibrant cultural scene. Yet, what intrigues me most about this novel are the ethical dilemmas Helene faces as she attempts to pass as the “Aryan” nurse Alice, dilemmas that complicate her status as a victim of Nazi oppression and make her complicit in the racial state’s projects of involuntary sterilization and Jewish genocide. The book’s chilling portrait of the Nazi engineer Wilhelm reveals the violence that lies just below the surface of his nationalist enthusiasms. Just as chilling, however, is the book’s depiction of what can happen to a woman who is told and shown–again and again–that her body is not her own.