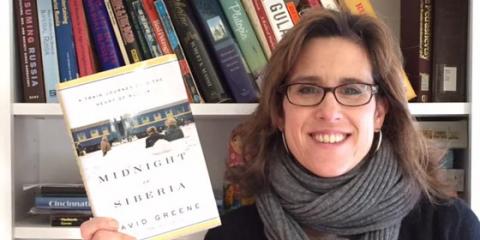

I have just finished reading Midnight in Siberia by NPR Morning Edition co-host and former Moscow bureau chief, David Greene, who takes us with him on a very long, very cold train ride across Russia through the cities and villages of Siberia (with quick detours to now war-torn Donetsk in Ukraine and Chelyabinsk, the “armpit of Russia”). The book’s premise is fairly simple: to find out how “ordinary” Russians are living and thinking twenty plus years after communism.

Traveling with his close colleague and translator, Sergei Sotnikov, and “armed with an ear, a deep sense of curiosity and no agenda,” Greene visits with an interesting and rather eclectic mix of individuals: an aging coalminer with a serious drinking problem, a former police officer rendered paralyzed after being falsely accused of kidnapping, a hard-working single mom running a small hotel on her own, a 21 year old man just out of the military and facing an uncertain job future, an environmental activist trying to save Lake Baikal from industrial waste, and the “Buranovo Babushki”, a group of tiny, elderly Udmurt widows who sing throughout Russia to raise money to rebuild their local church destroyed in Soviet times. For the most part, the people Greene meets are warm and welcoming and willing to open up to him about their experiences, their hopes and aspirations for their families and their country, and the many challenges they face in their daily lives (health issues, bureaucracy, corruption, and economic inequality, to name a few). For all the problems noted, however, he finds many of them deeply patriotic and proud of their country today, if sometimes nostalgic for the Soviet days when people “took better care of each other.” Relatively few, he tells us, look to more political democracy as a solution to their country’s problems. Although Greene acknowledges the disastrous impact of the rapid transition to democracy in the 1990s, he remains frustrated by what he sees as a lack of political will on the part of so many Russians today, and thus spends a good portion of the book trying to help us understand the many factors – cultural, spiritual, historical, economic – that keeps them from seeking a greater political voice.

Of course, no single book or series of interviews could begin to capture the full breadth of Russian society, and Greene doesn’t pretend that his does: his book unfolds as a investigative journey, intentionally organized around the stories of individuals in order to give voice to their unique experiences and perspectives. In this sense, his account emphasizes the diversity of the country today, even as it seeks to highlight the common ground that is “Russian” identity. To be sure, Greene’s is not an “insider’s view” of Russia – after all, he’s an American journalist who lived in Moscow for (only) three years, and he has a limited knowledge of Russian history and language. But he is a skillful storyteller, both keenly observant and deeply respectful of the people he interviews, and he asks good, important questions. All this results in a book that is smart and insightful. Although not the first travel account to lead Westerners into the “heart of Russia,” it is particularly timely, given the way that Cold War assumptions now threaten to reassert themselves.

The bottom line: if you would like to get to know the people of Putin’s Russia better – without traveling through Siberia on your own – this is an excellent place to start. And if you have already spent time in Russia, you’ll probably find yourself smiling as you relate to many of Greene’s experiences – while also learning something new too. Either way, this book is an enjoyable and quick read – proving, among other things, that books on Russia can be FUN as well as illuminating!